Music In Conversation

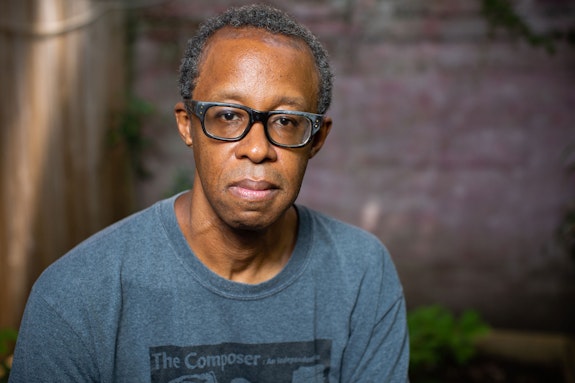

MATTHEW SHIPP with George Grella

Matthew Shipp is one of the most creatively restless musicians in contemporary music. He is most immediately identified with the free end of jazz, and his notable peers have included bassist William Parker, saxophonist Ivo Perelman, and the late saxophonist David S. Ware. His playing is rooted in the blues and features complex harmonies, a sound that is simultaneously rich and unstable—chameleonic. His robust musical personality and the intelligence and organic logic of his playing make him easy to spot in any context, whether improvising or playing with contemporary classical musicians like Daniel Bernard Roumain, or with hip-hop heavyweights like Beans. Since the early 1990s, he has been steadily prolific, and so far this year has released the solo CD The Piano Equation on drummer Whit Dickey’s new Tao Forms label, and appears with Dickey (and trumpeter Nate Wooley), on the double-CD Morph on ESP-Disk'. With venues and studios currently closed, he spoke on the phone from his home in May.

George Grella (Rail): The first question I want to ask is about your piano playing. When I pick up the sound and I identify, “Oh yeah this is Matthew Shipp,” there’s a couple things that really hit me first. One is that you have a very distinctive way with harmony, and another is that you move very fluidly between a lot of different idioms within a larger vocabulary. How did you get to that point?

Matthew Shipp: I’m obsessed with harmony. It starts with that. I’m utterly obsessed with tone colors coming out of the piano. It’s an avenue where I’ve put a massive amount of thought and work. I would start with that idiosyncratic, harmonic movement that I have. I can’t say exactly, but I would say getting a big sound—which harmony is a part of—is a massive part of what feeds my musical imagination. It’s just something that I’ve worked on distinctly and for my whole life. That’s the first thing.

As far as the movement between idiomatic kinds of gestures and things like that, I guess that I look at improvisation or composition as a dreamscape. When you dream at night many aspects of all different parts of your life come in and out of the dream—it’s very fluid and it goes through all things you’ve experienced and even things you haven’t. Sometimes you dream landscapes and people that have never even existed in your life. Since the musical space-time is a dreamscape for me, I try to get that same thing happening there where every aspect of anything that I’ve ever heard or exists in the common musical-unconscious could peek its head in a little bit. It’s a dreamscape and characters come in and out and they disguise themselves or mutate into something else. That’s my approach—letting nature take its course in a kind of more controlled way.

Rail: So there’s a free association thing that happens when you’re playing?

Shipp: Yeah, I mean I start from the premise that any gesture or musical idea is mathematically equal to any other. Just starting with that premise, anything can happen. Free association on one level yes, but on another level certain things are worked through. Sometimes it’s free association, sometimes it’s quite a lot of work—sometimes it’s the illusion of free association. [Laughs]…You put different elements together and sometimes you actually find out what they might have in common despite [any] superficial [differences].

Rail: Now, inside that is there room for building some more traditionally-minded logical structure? Like how Sonny Rollins might construct something out of variations.

Shipp: Well, yes. It’s really interesting you bring him up because he’s a straight ahead player and he said that when he first got the sax he didn’t know anything about songs, he just went into a room and started playing. He said something to the effect of that after years of getting things together that he still basically did what he did when he first got his sax and went into that room. Even though he obviously knows everything about songs. It’s hard to figure out exactly what percentage of things is this—as opposed to just letting go or just working within a certain framework. It’s hard to pinpoint especially if you’re trying to be intuitive in what you’re doing, you don’t really pull apart what you’re doing for your own sanity. I’m dealing in a lot of gray zones.

Rail: That feels intuitively strong based on just how I hear your playing, which is that there’s a lot of uncanny things going on or that you’re getting in-between the space of something and it’s not based on music you’ve heard before.

Shipp: Right.

Rail: I think your ideas about harmony do that too, you’re getting very specific colors out of the piano that I don’t hear very often from other musicians or classical composers.

Shipp: The sources of a lot of things aren’t obvious, but they’re like the dark sounds Ellington gets, McCoy Tyner's sound, a lot of things—there’s aspects of Bill Evans in my harmonic movement. At the same time, I’ve spent so much time dealing with blocks of sound and how to manipulate notes within it—there’s also a lot of pedal effects that I do that bring out overtones in chords… It also has to do with touch. You hit chords a certain way with a certain attack and it adds to the sound. Also sound is an internal thing that has something else other than the choice of notes and the physical effect on the instrument. There’s something internal that you can actually project, which is why there’s times where Keith Jarrett will play very sparse, but the sound coming out of the piano is completely polar opposite because they both are projecting something internal that shapes the whole thing. And how that all happens is the mystery.

Rail: If you’re looking at music as something that right now, you can only play in a studio and then send out to people after the fact, is there something that you can do in the recording process that’s specific to the sound that you want to produce from the instrument?

Shipp: Well, I’ve always had a related but separate structure in my head about me as a recording artist and me as a live performer. It’s a slightly different presentation, but there’s certain people that you think of more in regards to their recordings and certain people you think of in regards to live shows that you’ve seen. They’re related but slightly different things. So, if the recording paradigm is all that you have right now, then that’s what it is. There’s loads of people that have heard my records but have never seen me play live and vice-versa. I would assume that some of them would have similar ideas about who I am. For instance, Charlie Parker is one of my favorite musicians, but obviously I’ve never seen him live because he died before I was born. He’s still one of my favorite musicians based on a lot of not-well recorded albums [Laughs]. So, I’ve talked to people, who’ve seen him live and they would say that there’s something you might be missing.

Basically what I’m saying is that I just have to deal with what it is that’s in front of me. And I have faith that I can get the idea across no matter what. If somebody has a chance to hear me in an intimate room with a really good piano then that’s great and they might hear a certain dimension that somebody who’s just heard records might never have heard, but I don’t have any control over that.

Rail: What are your feelings about improvising and recording—taking something that’s spontaneous and then preserving it? Somebody puts it on and it’s repeating this thing that you only did that one time.

Shipp: It was in the history of jazz and I don’t really come at this as a modern improviser, I think of myself just as a musician—if I further subdivide that then I think of myself as a jazz musician. Recording something is one of the most important ways of keeping jazz alive. I don’t have any kind of ideology about recording or how it relates to being an idiom that people think of as spontaneous improvisation. I just don’t even think about it, recording is just something you do as a jazz musician and I do it. [Laughter] And if you come hear me live then it’ll be something different—don’t expect to hear a recording. The recording is there to document where you’re at during a period.

Rail: Yeah, I think that’s especially true for your catalog. I was just listening to some of the things that have been coming out in the last couple of years and then looking back at the Nu Bop (Thirsty Ear, 2002) record and things like that, I mean you’ve really explored a lot of possibilities for yourself. Is that all progress moving in one particular direction?

Shipp: Well, the direction that I’m always moving in is to find myself. [Laughter] So, whatever you do, that’s basically—I’m still me but you just change the clothes, same body—maybe one day I’m wearing a nice suit and the next day I’m wearing a sweatsuit. The bottom line is that I’m playing myself on the piano. As far as hitting different types of music, no one covered as much ground as Sun Ra. At some point he touched on the possibility of everything, even if he’s just hinting at it. He touched upon everything and no one else is going to touch upon more than he did. And like now, I’m just doing some solos, trios, and some duos. Over a period of a career, yes, you try out many different things, you stretch your mind over different areas and it’s all a feedback loop; you learn from it all and it feeds back to another part.

Rail: I want to get back to things a little more on the technical side because when you’re playing with other musicians it’s one thing but then when you’re playing solo it’s another, but how do you connect rhythm with harmony?

Shipp: I think everything comes out of one basic—okay, you have your sound, so in a way your basic sound is one organizing principle. It’s the locus and whatever your sound is it’s an abstract point that’s inside of you, and from that: rhythm, melody, and harmony come out of one basic building block and somehow find their place. But they’re all generated from the same source. That slightly gets into the whole harmolodics thing where there’s melody and rhythm and harmony related in coming out of a similar paradigm—or even interchangeable you might say. What is a melody but something sequenced in a certain way? It’s a matter of having a concept of music and having a basic sound embedded in your subconscious mind. The other parameters of that naturally come out of the organizing principle. They just flow from that point. So it’s sound first, and rhythm probably second because melody and harmony can be seen as an aspect of rhythm. Harmony in the sense that you can look at melody as rhythm and then harmony can be looked at as a natural point of these densities coming together. It’s sound then rhythm then vibration and everything flows out of that. Everything that flows out of that is your music.

Rail: Would you then describe your thinking—your dreamscape idea, your idea of harmony and this flow of rhythm sounds like you’re describing music that is a horizontal orientation rather than a vertical one. I guess a contrast would be between modal music and baroque ideas about rhythm and then the more straight up and down chords that happen later in Western music.

Shipp: Right. I never thought of it that way, but I guess you could. I always thought of it as a kind of mixture of both. I think George Russell described what I do as “horizontal something.” [Laughter] So maybe that is true.

Rail: When I listen to you very closely, it’s a thing—coming out of jazz you have the whole thing with Red Garland just hitting those chords right on the beat or with some clear syncopation and you’ve got that fluid harmony going on where you’ve got two notes down and you’re building a little counterpoint there or you’ve got leading tones going on, moving line by line and adjusting the feeling of the chord or the harmony through different permutations. That just seems to be flowing out through your hands.

Shipp: Right, right. I’m also thinking that the counterpoint is infinite and always going on so any improvisation or performance or actualization is stepping into a process that’s always going and the lines are always moving—it’s a perpetual feud going on. That’s the way your brain works. It’s trying to marry the elements of music—the basic elements of rhythm harmony and rhythm to the brain. [Laughs]

Rail: If you’re thinking in terms of this dream-like idea, do you surprise yourself when you’re playing?

Shipp: Sometimes, yes. A lot of times, no. But yeah, sometimes you wake up—I’m saying you wake up, I mean if you’re just playing…then you realize—what was that? Sometimes in a good way, sometimes in a jolting way. And sometimes you’re just not sure but that’s sometimes the best time, because you don’t want to be playing stuff you’re sure of all the time. Sometimes you let certain days, stuff just happens and you’re even—the amount of times you can travel out of your body, step down and look at yourself, and it’s like wow, that’s not every day. But it does happen sometimes, or at times, when you really kind of step back, and are looking at it while it’s happening. And it’s not an illusion. It’s not like you’re just high or something and you’re having a great time, and you listen to the tape and it’s horrible. [laughs] There are times when you’re playing, and you step back and look at it, and then if you hear it back it actually is like, “wow, yeah, how did that happen?”

Rail: Are gestures or familiar musical ideas, do you have a bag of those? Is that something useful for you?

Shipp: Yeah; you have no choice but to have that. You hear people sometimes say they never repeat themselves. That’s garbage. Everybody repeats. [Laughs] Jimi Hendrix, you know, everybody—[Laughs]. For somebody not to have a—I don’t want to call it a bag of tricks—but you know, stuff that they can rely on…if an improviser could just get up on stage and make everything up fresh from the start, every performance and never repeat themself, they wouldn’t be human, you know. You would’ve stepped into another realm of existence that you can’t quite get on the planet Earth, at least in the type of dense vibrational bodies that we got. So I mean, I understand the need for myth-making with this, but there’s just no gain around the fact that as a human being…you know, if you divide the brain and mind, the mind is actually infinite, but the brain is enclosed. There’s just a certain amount of things you do as an improviser. You’re always trying to get out of them, but that’s a process. There’s no magical person that gets on stage and is playing something new every time; that doesn’t exist.

Rail: What’s the value, along with that, of, let’s call it tradition. What’s the value in showing the tradition?

Shipp: Well, I think it’s [a] choice with everybody. Some people have a deeply psychological need to let people know that they know the tradition or they can play their instruments in many ways. And some people just don't care. They do what they do and it’s like take it or leave it, this is what it is. Who knows exactly how somebody ends up getting the psychological need to have a presentation in a way, that, “I’m playing this, but I want you to know I’m informed by it.” It’s really hard for me to get to the minds of people who play music because everybody’s so different. Everybody has a different set of needs as far as what they want to project to the audience or even what they want to get out of the experience. So it’s kind of hard. I can just say for myself, I get on stage and I want to be myself, first of all, but I actually really do love the jazz tradition. I just love that tradition. So it’s just a matter of me trying to be myself but kind of projecting the things that I love also.

Rail: This is the big question—why do you play music?

Shipp: Oh wow…I gotta think before I say anything. Well, first of all, I started playing really young. So there’s no kind of thought process. You know, you just go into it. The first thing, I really was touched by certain music I heard in my parents’ church. And it kind of raised a religious feeling in me. I would say to begin, it was just…music. As far as making a career choice, that’s a whole different thing. I would answer that—you didn’t actually ask why did you go into music as a career. You asked why you play it.

Rail: Yeah, why does it come out of you.

Shipp: Well, in the realm of things to do as a human being, it’s one of the things, you know? [Laughs] It’s one of the things people do. It’s easy how you gravitate toward something. You like it, and/or you’re doing it, and you see that you have an aptitude to do it. Like if you ask a boxer, why do you get hit in the head to make money? Easy, if they walked into the gym as a kid, and somebody taught them something. They saw that they were decent at it, so they figured they could make a living out of it. It usually comes down to that. So I would say with music it’s some…I developed a love for it as a kid; I got involved in it. I was somewhat decent at it, and figured I had more aptitude for it than a lawyer or something like that.

Rail: Along with hearing music with your parents in church, what, as a kid, what secular music—let’s put it that way—did you hear that excited you?

Shipp: When I was a little kid I was just interested in the regular music that the kids, everything. I mean I was really into the Jackson 5, that was my thing. Especially the whole culture around the afros and stuff. I wanted to have a big afro like Michael did but my father wouldn’t let me grow an afro. There was nothing out of the ordinary when I was a kid. I started really listening to jazz when I was around 12. Most kids I know did not listen to jazz. But at the same time, I listened to the same music as my friends, and had a social life around certain aspects of rock or pop that other friends of mine would’ve had. And my friends thought it was cool that I was going home and listening to John Coltrane. And some of my friends who might’ve said, “listen to Jimi Hendrix,” were able to also get into Coltrane or whatever. I also had an uncle that was a pianist; he was a church organist. And he used to play some Chopin and stuff…I was really into classical music too. Just because my mother had a bunch of classical albums and my uncle played a little. So at a pretty early age, I was really into Beethoven and Chopin and stuff like that.

Rail: And practicing, is that…were you practicing through the classical book, like Bach and Czerny and stuff like that?

Shipp: When I got serious, I was going through everything. I mean…I didn’t go through the Czerny. I practiced from it a little bit, but I went through the handbooks. I even found, which was hard to find, there were some technical books which Franz Lizst had written. I found those, went through all—I mean, I was serious. Very serious. So, I spent a lot of time with Bach, which should be obvious if you listen to me [Laughs].

Rail: You also mentioned Chopin, I think there’s those colors there. And that sense of the kind of harmony as not a resting place, but as kind of a constant flow…

Shipp: There’s a romantic hyper-extension where harmony actually kind of sounds like a realm of insanity in Chopin sometimes. The thing about Chopin that I found interesting is that you can’t really reconcile it with classical music history. It’s kind of its own island completely. Like, the way you think of Mozart or Beethoven, you don’t think of Chopin…it’s just kind of its own bizarre thing that just happened. It’s its own poetic island. I always kind of say, “and it’s Poland,” which is so different from Germany, or even France. It just kind of came out of nowhere almost, this island of this insane piano music, of this possessed guy you can’t quite put your hand on. I always found him fascinating. I actually never read a biography of him, which is kind of bizarre cause I was so into him as a kid. There’s a lot of biographical aspects that I couldn't tell you cause I knew—I knew the basics of his life, but I never actually delved in farther than the fact that I was extremely into his music.

Rail: When you’re interested in listening to somebody else, who do you reach for?

Shipp: Well the go-tos are the usuals. There would be nothing surprising about who the go-tos are. There’s certain things I listen to for inspiration that probably most people never even heard or heard of. There’s one album, my teacher [guitarist] Dennis Sandole, who was my composition teacher. He was John Coltrane’s teacher also. And he did an album in the ’50s that was never released but Cadence released it about 10 or 12 years ago. I actually wrote the liner notes. But I had it on acetate as a teenager before, or I had it on a cassette from then…I used to listen to that constantly as a kid. And still, if I need to just chill out and remind myself who I am I listen to that. There’s also something I used to listen to a lot by a pianist hardly anybody’s ever heard of. His name was George Genna. And he actually used to be the music director for Sammy Davis Jr.

He studied with my same teacher. And there was a live performance he did when I was a teenager of his own compositions, that’s completely—like right now he’s doing a really straight ahead jazz thing. I happened to see this concert—my friend taped it when I was a teenager—and it was just really a completely original style that he was using back then that he doesn’t really play in anymore. I had that on a tape as a teenager. I used to constantly, constantly listen to that. But again, it’s something that nobody would ever…it’s one of those things. When I really need to reconnect to the jazz tradition, to find myself, it’s Bud Powell and Monk.

Rail: It’s funny, I was listening to a couple of your things a couple of days ago, and I kept thinking Bud Powell, Bud Powell, Bud Powell.

Shipp: No, no, no, no, Bud Powell is like my guy. He’s always my guy. [Laughs] Monk is second but Bud Powell is my guy. When I really need to reconnect to the jazz tradition it’s Bud Powell and Monk and in a different way. But Bud Powell is my guy. Everything I said about Chopin, as far as…well, I mean there’s a direct tradition that Bud Powell falls directly within. But he’s still just this island of incredibly organized insanity. It’s just utterly amazing. As far as who’s on the scene, I don’t really…I mean, I could tell you who I really like on piano. I really like Kris Davis and Craig Taborn, and they’re friends of mine. But I really really…and Gonzalo Rubalcaba—oh, there’s this guy, you know who nobody ever talks about, is Marc…oh, God I can’t believe I’m spacing on his last name. Pianist…He played with John Abercrombie. I can’t believe I’m spacing on it. He is just…he has an album that I have.

Rail: Here we are, doing the Google thing. Marc Copland?

Shipp: Yeah, Marc Copland. Marc is phenomenal. And Gonzalo Rubacalba, Jason Moran, Craig, and Kris Davis I’m really, really excited about. In fact, I think [Kris is] one of the greatest Monk interpreters I’ve ever heard, when I heard her play Monk. Oh, also, as far as another person to reconnect me to the roots, both at one point it was Randy Weston, but Mal Waldron is kind of at the seed of everything that I…I just find everything goes to this system and gets somehow transformed. He’s just a generator of language that I find is always stimulating.

Rail: Yeah, very interesting to hear you mention that.

Shipp: And then when I feel the need to remember that I’m partially insane and it’s good to be insane,I listen to Sun Ra.

Rail: Let me just ask you one more thing, which is, what are you thinking about for either the short-term or the long-term future, what you can do as a musician?

Shipp: Well, I’m just continuing to practice, trying to get better. That’s my major goal every day is to get up and to further dig deeper. As far as…you know, I got a lot of things planned for this year. I’m actually taking this time to sit back and kind of try to think things through. When the world gets back to normal—well, first of all, when the world gets back to normal, like a lot of people think people are gonna be transformed and all that. I think people are just gonna go back to exactly—

Rail: I’m with you on that. That shit doesn’t happen.

Shipp: I don’t think anybody will learn anything, or, you know…So this started from that premise. And then so with that in mind, I turn 60 this year, so it’s not like I’m a spring chicken or anything. I’ll be a senior citizen in a few years. Even if you live another 30 years, even if you’re still kind of in the last phase of your career. It basically comes down to a couple of things: you either keep recording or perform live. I’m not going into a career as an educator. I don’t have any desire to do that. I don’t have the desire to…basically on one level I’m just gonna continue doing what I’ve been doing.

Rail: Fair enough, fair enough.

Shipp: There’s no magic number in all this. Or, there are, but they’re below the surface.