I got to know Hans Blüthner sometime in the late 1990s. He lived in a retirement home in Weinheim an der Bergstraße, where I visited him a few times. Blüthner was pure jazz history, a contemporary witness to the Berlin jazz scene from the 1920s through the 1960s, a pen pal of Louis Armstrong, collector, organizer, but above all a big jazz fan. "Unfortunately, I gave away my documents many years ago," Blüthner told me somewhat wistfully. The only jazz-related items in his room were CDs with reissues of his favorite music. Blüthner was hardly able to walk; his body was no longer able to keep up, but his mind was all there.

Hans Blüthner

Hans Blüthner (left, 1952 with Louis Armstrong) was born on June 23, 1913 in Berlin-Charlottenburg. At the age of eleven, he was bed-ridden for months due to severe osteomyelitis. His stepfather made him a detector with which he could listen to the radio via headphones, and he soon immersed himself in the pop and dance music broadcasts on "Welle 505 Berlin", the first German radio station to broadcast live from the Palais de Dance or the Pavillon Mascotte in Berlin's Friedrichstadt district from 1923. It was the popular music of the time that got him hooked and never let go, and he probably didn't even know at the beginning that it was jazz and what role jazz would play in his life.

Hans Blüthner (left, 1952 with Louis Armstrong) was born on June 23, 1913 in Berlin-Charlottenburg. At the age of eleven, he was bed-ridden for months due to severe osteomyelitis. His stepfather made him a detector with which he could listen to the radio via headphones, and he soon immersed himself in the pop and dance music broadcasts on "Welle 505 Berlin", the first German radio station to broadcast live from the Palais de Dance or the Pavillon Mascotte in Berlin's Friedrichstadt district from 1923. It was the popular music of the time that got him hooked and never let go, and he probably didn't even know at the beginning that it was jazz and what role jazz would play in his life.

At the end of the 1920s, Blüthner discovered Alberti in Rankestraße near the Gedächtniskirche, the most modern specialist music store in Berlin at the time. "Here," he recalled in 1986, "you could find everything to do with hot, dance and jazz music: musical instruments, sheet music, records, jazz literature including specialist magazines from both sides. Musicians went in and out. It was a new world for me." (Blüthner 1986: 9) He listened to the international bands of the capital, Weintraub's Syncopators, Efim Schachmeister, Sidney Bechet, Sam Wooding, Arthur Briggs. He became a jazz fan for good.

Then came the "Third Reich" and the attempt to ban jazz, but bands like those of Teddy Stauffer, Arne Hülphers and others "brought us everything that was played in the USA". Blüthner had to leave the Falk-Real-Gymnasium, which he attended, in the fall of 1933, "five months before his Abitur due to political disputes". In the fall of 1934, he began an apprenticeship as a bank clerk at Diskont- & Kredit-Aktiengesellschaft, which then took him on as a commercial clerk. Until 1939, Blüthner received both the British Melody Maker as well as the American Down Beat by mail and thus kept up to date with the American jazz scene.

And he started to collect records. "On Electrola, Columbia, Odeon, Brunswick, Imperial etc. you could get pretty much anything your heart desired - with certain later restrictions as far as non-Aryans were concerned." (Blüthner 1986: 10) From 1934, he was a member of the Melody Club (also "Melodie Club", later "Magische Note"), whose members met every Thursday in a café on Kurfürstendamm and showed each other their record treasures.

In March 1940, Blüthner fell in icy conditions and broke his arm. The injury and his osteomyelitis saved him from military service. In the meantime, he worked for his uncle's Massivbau-Gesellschaft m.b.H., soon as commercial manager. In 1944, one of his uncle's business partners betrayed him for listening to forbidden enemy radio stations (BBC); he only escaped imprisonment because the prisons were already full of political prisoners. By Christmas he was free again. Towards the end of the war, only Blüthner and Gerd Peter Pick were still in Berlin from the circle of friends of the Melody Club (Kater 1992: 76); the rest had left the capital, if not the country, or had died in the war.

After the war, Blüthner (on the right in the photo with Lil Hardin-Armstrong, ca. 1954) co-founded the Hot Club Berlin, which received a license from the military government in 1947. He continued to work in his uncle's construction company until it filed for bankruptcy in 1969. He was then employed as a scheduler and head of the programme department at the theater visitors' organization of the Freie Volksbühne until he retired in 1980 at the age of 67. Together with his wife, he moved to Hemsbach an der Bergstraße. "We have a little difficulty understanding the local Gebabbele [dialect]", he wrote to a friend shortly after the move. "Unfortunately, there is still no dictionary for Baden-Palatinate Hessian." (Blüthner 1981) Hans Blüthner died on April 9, 2002 in a nursing home in Weinheim at the age of 88.

After the war, Blüthner (on the right in the photo with Lil Hardin-Armstrong, ca. 1954) co-founded the Hot Club Berlin, which received a license from the military government in 1947. He continued to work in his uncle's construction company until it filed for bankruptcy in 1969. He was then employed as a scheduler and head of the programme department at the theater visitors' organization of the Freie Volksbühne until he retired in 1980 at the age of 67. Together with his wife, he moved to Hemsbach an der Bergstraße. "We have a little difficulty understanding the local Gebabbele [dialect]", he wrote to a friend shortly after the move. "Unfortunately, there is still no dictionary for Baden-Palatinate Hessian." (Blüthner 1981) Hans Blüthner died on April 9, 2002 in a nursing home in Weinheim at the age of 88.

The notebook

He had given away his documents many years ago, ad Blüthner told me, and when I asked him, he couldn't remember exactly to whom - someone who cared about German jazz, he said. Fast forward to the early 2000s, quite shortly after Blüthner's death: we received a call from Wuppertal that an apartment there was to be liquidated, the occupant of which had apparently collected a lot of information about jazz. Mostly paper, they said, but really, really a lot of it. We rented a small truck and drove to the Lower Rhine. And loaded up: boxes upon boxes full of magazines, folders with notes, photocopies, books, letters, addressed to the "Kultureller Wirkungskreis Jazz". Behind this was the collector Martin Pecherstorfer, who was in contact with other experts - he had also corresponded with the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt during his lifetime - from whom he received a wealth of information about the history of jazz in Germany and Eastern Europe. In particular, Pecherstofer also had good contacts behind the Iron Curtain, exchanging ideas with collectors such as Wolfgang Muth or jazz friends from the CSSR or Poland.

He had given away his documents many years ago, ad Blüthner told me, and when I asked him, he couldn't remember exactly to whom - someone who cared about German jazz, he said. Fast forward to the early 2000s, quite shortly after Blüthner's death: we received a call from Wuppertal that an apartment there was to be liquidated, the occupant of which had apparently collected a lot of information about jazz. Mostly paper, they said, but really, really a lot of it. We rented a small truck and drove to the Lower Rhine. And loaded up: boxes upon boxes full of magazines, folders with notes, photocopies, books, letters, addressed to the "Kultureller Wirkungskreis Jazz". Behind this was the collector Martin Pecherstorfer, who was in contact with other experts - he had also corresponded with the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt during his lifetime - from whom he received a wealth of information about the history of jazz in Germany and Eastern Europe. In particular, Pecherstofer also had good contacts behind the Iron Curtain, exchanging ideas with collectors such as Wolfgang Muth or jazz friends from the CSSR or Poland.

So now all the material went to Darmstadt, and it was a long time before we got even a hint of the extent. Massive Down Beats, Jazz Hots, but also Melodie und Rhythmus and other Eastern European magazines. In addition, folder after folder with the research documents of private researchers and discographers, records of their work that they thought they would rather send to Wuppertal than dispose of in the trash.

And then there were two boxes labeled "Blüthner". "Unfortunately, I gave away my documents many years ago," he had said to me wistfully from his bed. Here they were, having found their way to the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt by a strange detour via Wuppertal. Correspondence with Armstrong from the 1950s and 1960s, memories that Mitteilungena magazine published by Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, handwritten music books with hits and dance music, a lecture manuscript by Dietrich Schulz(-Köhn) from 1936 on "Einführung in die Swing-Musik" (held at the Delphi-Palast on January 20, 1936; manuscript revised in June 1936).

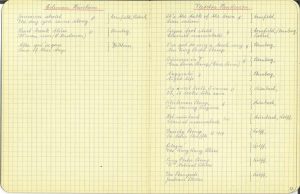

And a strange notebook with a list of records and a row of names behind each record. At first, we had no idea what it was all about. It was only gradually that we connected the names behind the entries with our knowledge of the Berlin jazz scene of the 1930s and realized: This was the inventory catalog of the "Berliner Hotfreunde", as Blüthner called the group in a memoir from 1947.

The Melody Club

"Since 1934," it says, "there has been a circle of real hot friends in Berlin who used to meet once a week in Café Hilbrich on Kurfürstendamm (in the Blue Room) to enjoy and discuss their records, which were played on a portable machine. At that time, it was Mr. Adalbert Schalin from the Alberti publishing house, the Dorado of all jazz enthusiasts (all domestic and foreign records, sheet music, jazz newspapers, instruments, etc. were available here), who set up this 'Melody Club', as it was called." (Blüthner 1947) [Photo: Siegfried Schröter, Hans Friedemann, Hans Blüthner in the late 1930s]

"Since 1934," it says, "there has been a circle of real hot friends in Berlin who used to meet once a week in Café Hilbrich on Kurfürstendamm (in the Blue Room) to enjoy and discuss their records, which were played on a portable machine. At that time, it was Mr. Adalbert Schalin from the Alberti publishing house, the Dorado of all jazz enthusiasts (all domestic and foreign records, sheet music, jazz newspapers, instruments, etc. were available here), who set up this 'Melody Club', as it was called." (Blüthner 1947) [Photo: Siegfried Schröter, Hans Friedemann, Hans Blüthner in the late 1930s]

In 1950, he recalls in even greater detail: "What could be more obvious than to found a hot club in 1934, where, as followers of authentic jazz, one could play the unique records of Louis Armstrong or Bix Beiderbecke, which were not subject to any fads [sic!], compare them with modern recordings by Benny Goodman & Tommy Dorsey and realize again and again that art can have an ideal as well as a material side. Of course, the circle around this club could never go public, because the followers of jazz were identical with democracy and freedom. Such ideals were not allowed to exist in the Third Reich. So the Hot Club Berlin, which was then called the "Melodie Club", was not allowed to be loud and could only work in silence. The prospects of setting a goal became increasingly slim. The circle, in which neither racial nor class hatred was known, became smaller and smaller due to persecution and the impending war, and was reduced to a minimum in a very short time. Even if it were possible to enforce a ban on jazz music and everything connected with it, the spirit and love of this music and the bond between the individual followers within the club could not be prevented. With great difficulty, even in the middle of the war, a 'newsletter' was published to create a link between all friends of jazz. The never-ending war finally ruined everything, and so in the end everything held internally in Berlin jazz circles had to be discontinued." (Blüthner 1950)

But back to the notebook: it ultimately contains a kind of directory of the private collections of the hard core of this Melody Club, compiled by Blüthner, who was thus able to refer interested parties to the owners of the records, along the lines of: "If you are looking for this or that, contact xvz, he has the recording, you can definitely listen to it with him." In 1989, Blüthner mentions the notebook in a conversation with Bernd Polster about the club meetings in the Café am Kurfürstendamm: "We met every Thursday in a café on Kurfürstendamm. That no longer exists today. We had the Blauer Salon on the second floor and had a noodle box [record player]. And then we played records, shellac of course. And there was one guy who kept the books. Everyone who was in the club had to hand in a catalog of their record holdings. And the bookkeeper transferred that to a general catalog. And when a program was made, he would say 'Bring the record. This one and this one', and then everyone had to make a program." (Polster 1989: 31-32) It seems that Blüthner himself was that bookkeeper, and what we had in the notebook was this "general catalog" of the Melody Club's record holdings from the mid-1930s.

Blüthner recalls that the members of the club were thoroughly scrutinized for their specialist knowledge. It was "a mixed circle", "including many young Jewish gentlemen" (Polster 1989: 32). The club met in the café for perhaps two years, after which the owner claimed that a skat club had rented the Blauer Salon and they had to leave. They met for a while in a dance school next door, then moved to another café, but the owner was not satisfied with the young people's consumption (Polster 1989: 32). Finally, they met at the home of one of the members. The Melody Club (Magische Note) continued to exist into the war, although the number of members continued to decline: Blüthner: "The Jewish gentlemen were then gone, the others had to join the military. During the war we were down to two or three men." (Polster 1989: 33)

“Die Berliner Hotfreunde”, 17. Januar 1947

(complete PDF opens by clicking on the image)

“Berlin und Jazz”, 22. September 1950

(complete PDF opens by clicking on the image)

The notebook

(complete PDF opens by clicking on the image)

The members

So who were the Melody Club collectors immortalized in this notebook? They were, in alphabetical order: Auerbach, Blüthner, Boger, Cornfield, Gittermann, Petruschka, Pfrötschner, Robert, Sternberg, v. Drenkmann and Wolff. We have done a little research:

Heinz Auerbach was a Berlin Jew (Kater 1992: 74) and, together with Franz Wolff, a proponent of black jazz in particular (Kater 1992: 85) - indeed, this was definitely an aesthetic political issue among jazz fans in those years. He left Germany in 1938, founded the Hot Club de Janeiro in Rio, Brazil (Blüthner 1950) and finally ended up in Buenos Aires (Lange 1966: 71), where he headed the Hot Club there, which pursued very similar activities to the Melodie Club: "meet to compare, discuss, and argue over recorded music" (Crosby 1953: 23), but was mainly limited to older jazz (Thiers 1960: 262).

Hans Blüthner we have already got to know. When he became a member of the Melody Club in the fall of 1934 at the invitation of Adalbert Schalin, he introduced Jimmie Lunceford's record "Swingin' Uptown" to his new friends (Kater 1992: 85; listed in the Kladde on page 33). Blüthner was very self-confident about his love of jazz. He had the British Melody Maker and read this newspaper on the subway - hardly anyone else could read English anyway. He explains that there were no Nazis in jazz circles: "That's a rule, I'd like to say, anyone who is interested in jazz can't be a Nazi." (Polster 1989: 34)

Carlo Boger (1911-1943) was active as a stage designer, actor, illustrator and cartoonist in Weimar, Vienna (1928), Stuttgart (1929), Leipzig (1932-33) and Berlin. In Leipzig, he worked as a stage designer and actor in Bruno Tuerschmann's Kammerspiel and also appeared in the literary cabaret Litfaßsäule in March/April 1933 (https://www.buchprojekt1.de/produkt/c-boger-1911-1943-das-mistvieh-n-2-karikatur-um-1930-tusche-figuerlich/). Michael Kater describes him as an "alcoholic, author of short stories, graphic artist, lover of literature and theater" (Kater 1992: 97). In 1933, Boger married Else Eichler, a writer and publicist for women's issues who was twelve years his senior. Boger's graphics often focused on jazz; a portrait of the singer and trumpeter Valaida Snow dates from 1936 (https://www.pinterest.at/pin/400187116881463220/). Boger was considered missing after the war; Kater explains that he died at the front (Kater 1992: 97).

Robert Kornfilt [Bob Cornfield] was a close friend of Blüthner. He was originally from Turkey [Kater 1992: 75]. Horst H. Lange writes in his history of Jazz in Germany that Kornfilt had initiated the founding of this "first important German jazz club [...] as early as 1932" (Lange 1966: 69), before it was then "properly founded with the help of the enterprising Alberti-Musikhaus procurator, Adalbert Schalin" (Lange 1966: 69-70). Kornfilt was an amateur arranger, good enough for the popular bandleader Erhard Bauschke to include one of his arrangements in his repertoire (Kater 1992: 89). After the war, he returned to Turkey.

Gittermann: Unfortunately we could not find out anything about this name.

Sigmund Petruschka (1903-1997) was a trumpeter and arranger. Born in Leipzig, he received piano and cello lessons as a child and sang in the Gewandhaus Choir under Arthur Nikisch. In 1923, he moved to Berlin to study mechanical engineering and also attended the Stern'sche Konservatorium, where he took trumpet and double bass lessons (https://www.nli.org.il/en/a-topic/987007266398905171). Together with Kurt Kaiser, he co-founded the band Sid Kay's Fellows, in which Friedrich Holländer, among others, worked as pianist and arranger. In the 1930s, Petrushka wrote under pseudonyms for the Deutsche Gramophone Gesellschaft, for UFA films, but also for popular bands such as that of James Kok (Lange 1966: 52). He emigrated to Palestine in 1938 (Kater 1992: 39-40) and soon directed the orchestra of the Palestine Broadcasting Service. Petrushka died in Jerusalem in 1997. He is only mentioned twice in Blüthner's notebook: he was obviously a big fan of the Casa Loma Orchestra, whose records "Ol'Man River" / "I Got Rhythm" and "Dallas Blues" / "Limehouse Blues" he owned.

It is quite possible that behind "Pfrötschner" the author Gerhard E. Pfrötzschner who, in the 1930s, was the Germany editor of the London Melody Maker and the British Metronome As "raving reporter", Pfrötzschner had been writing for the magazine Der Artist about the Berlin jazz scene and wrote record reviews. In September 1934, he wrote the article: "How does the German musician feel about jazz music? Doesn't rejecting it mean unemployment?" (cf. Jockwer 2004: 298). In 1935, Prötschner attended concerts by the British bandleader Jack Hylton in Berlin (Jockwer 2004: 300). Nothing is known about Prötschner's whereabouts after the war.

Robert: Unfortunately we could not find out anything about this name.

Dieter Sternberg: Unfortunately, we could not find out anything about this name. We know about his first name from the caption on the back of the photo shown at the end of this piece.

Günter von Drenkmannknown as "Bobby" (1910-1974) came from a family of lawyers and also studied law himself. He wanted to become a judge, but had no chance in the 1930s because he refused to join any Nazi organization (Schmid 2010). After the war, however, Drenkmann quickly made a career for himself, as a judge at the regional court, then a district court judge, then a chamber court judge and finally, from 1967, President of the Berlin Chamber Court. Hans Blüthner wrote to Drenkmann on the occasion of his appointment to the last step in his career in January 1967: "Between you and me, I always have to remember that about 30 years ago we thought that all higher influential positions should be held by people with a little passion and love for our common hobby! Well, you managed it and made it." (Blüthner 1967) On November 10, Drenkmann was murdered by terrorists of the Bewegung 2. Juni during an attempted kidnapping.

Jakob Franz Wolff, called "Franny" (1907-1971) trained as a photographer in Berlin. In 1925, together with his friend Alfred Löw, he had seen pianist Sam Wooding's band at the Admiralspalast, after which he became a lifelong jazz fan. Löw had already emigrated to New York in 1936, Wolff followed him two years later on one of the last passenger liners to leave Nazi Germany for the Big Apple. The two went on to make history, founding the Blue Note record label, which initially recorded traditional jazz and boogie-boogie, but soon also the young, more modern jazz musicians, releasing style-defining records from the 1950s onwards. Löw, who called himself Alfred Lion in the USA, was the businessman among them, and Wolff, who now traded as Francis Wolff, was an equal partner. Both took the musicians who recorded for them seriously as artists, even paying them for their rehearsal times (previously completely unusual in this music), and Wolff also made a name for himself as a masterful photographer whose pictures became almost iconic, not only, but also because they adorned the records of his own label.

As we will see below, the notebook dates from 1936, which is why jazz friends who subsequently became members of the Melody Club or the Magische Note are not listed here. Blüthner mentions them in his memoirs from 1947: for the 1936 Olympics, for example, he records visits from guests such as the American trombonist Herb Fleming, the Frankfurt saxophonist Eugen Henkel, the pianist Fritz Schulz-Reichel, Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, but also Duncan McLougald, a "friend of Benny Goodman and Helen Ward".

From 1938, they met privately, mostly at Blüthner's home, and he mentions Gerd Pick, Folke Johnson from Sweden, the Belgian pianist Coco Collignon, and Varvavar Varasiri from Siam as frequent guests. "Fräulein Thieme and Mr. von Drenkmann", he writes, were left over from the circle of "old people" in 1947, i.e. from before 1936. A "Herr Edelscharf" had joined them in 1938. And then he mentions what happened to the other members: "It is very unfortunate that the atmosphere of the old 'Hot-Kreis' will never return, especially as almost all the former members of importance have turned their backs on Berlin. Franz Wolff went to New York at the beginning of the war, Heinz Auerbach went to South America, Bob Cornfield went back to Turkey, Gerd Pick is in Frankfurt, Olaf Hudtwalcker in Mannheim, Hans Friedemann in Luckenwalde, Vasiri in Washington, Wilfried von Weselstedt and Hans Horseck were killed on the Eastern Front, Carlo Boger is missing in action, Egon Wilrich fell victim to an air raid. We can only hope that one or the other will find their way back to Berlin from captivity." (Blüthner 1947)

In 1945, Blüthner founded the Hot Club Berlin together with old and new friends, which held its first meeting on October 27, 1945 (Blüthner 1947).

The music

The notebook then contains a list of the records owned by Melody Club members. They are listed according to the bandleaders, with two titles per record, followed by the owners; sometimes one, sometimes several. The compiler (i.e. Blüthner) left as much space as he thought the respective bands needed, i.e. more for well-known and popular bands than for less well-known ones. On the very first page there is already one of the hits, which is owned by six of the members: Duke Ellington's "Tiger Rag I and II" (Wolff, Sternberg, Cornfield, Robert, Blüthner, Boger). Blüthner only lists the titles on the records, no further discographical details, such as label or record numbers. He groups the two titles of each shellac record with curly brackets. And if titles from different bands were released on a record, he lists them twice, under the names of the respective bandleaders, but with a reference to the respective reverse side.

The notebook then contains a list of the records owned by Melody Club members. They are listed according to the bandleaders, with two titles per record, followed by the owners; sometimes one, sometimes several. The compiler (i.e. Blüthner) left as much space as he thought the respective bands needed, i.e. more for well-known and popular bands than for less well-known ones. On the very first page there is already one of the hits, which is owned by six of the members: Duke Ellington's "Tiger Rag I and II" (Wolff, Sternberg, Cornfield, Robert, Blüthner, Boger). Blüthner only lists the titles on the records, no further discographical details, such as label or record numbers. He groups the two titles of each shellac record with curly brackets. And if titles from different bands were released on a record, he lists them twice, under the names of the respective bandleaders, but with a reference to the respective reverse side.

Here, then, are the artists listed, in alphabetical order by band name:

- Henry Red Allen: 5 records

- Pauline Alpert: 1 record

- Bert Ambrose: 15 records

- Louis Armstrong: 31records

- Gus Arnheim: 1 record

- Artiphon Orchester: 1 record

- Harry Ascher: 1 record

- DeFord Bailey: 1 record

- Balalaika Orchester: 1 record

- Billy Barton: 1 record

- Bix Beiderbecke: 4 records

- Benson Orchestra of Chicago: 1 record

- Ben Bernie: 5 records

- Bluejeans: 1 record

- Boswell Sisters: 15 records

- Arthur Briggs mit seinen Savoy Syncopators: 1 record

- Buddy’s Brigade: 1 record

- Hans Bund: 1 record

- Rev. J.B. Burnett: 1 record

- Cab Calloway: 12 records

- Francisco Camaro: 2 records

- Benny Carter: 4 records

- Casa Loma Orchestra: 21 records

- Castlewood Marimba Band: 1 record

- Cellar Boys: 1 record

- The Charleston Chasers: 1 record

- Chicago Feetwarmers: 1 record

- Chocolate Dandies: 7 records

- Junie Cobb: 1 record

- Oliver Cobb: 1 record

- Eddie Condon: 2 records

- Coon-Sanders Orchestra: 3 records

- Charles Creath’s Jazz O’Maniacs: 1 record

- Zez Confrey: 1 record

- The Cotton Pickers: 3 records

- Julio de Caro: 2 records

- The Decca Dance Band: 1 record

- Dickson’s Harlem Orchestra: 1 record

- Dixie Rhythm Kings: 2 records

- Vance Dixon: 1 record

- Johnny Dodds: 2 records

- Dorsey Brothers: 1 record

- Duke Ellington: 91 records

- Reginald Foresythe: 1 record

- Caroll Ginnons: 3 records

- Lud Gluskin: 2 records

- Benny Goodman: 1 record

- Stéphane Grappelli: 2 records

- Henry Hall: 1 record

- Coleman Hawkins: 3 records

- Fletcher Henderson: 26 records

- Horace Henderson: 1 record

- Earl Hines: 9 records

- Sol Hoopie: 1 record

- Claude Hopkins: 2 records

- Brigitte Horney: 1 record

- Spike Hughes: 11 records

- Jack Hylton: 4 records

- Isham Jones: 1 record

- Jack Jones: 2 records

- Oskar Joost: 1 record

- Greta Keller: 1 record

- Eddie Lang: 1 record

- Layton & Johnstone: 1 record

- Ted Lewis: 2 records

- Guy Lombardo: 1 record

- Jimmie Lunceford: 10 records

- Cecil Mack: 1 record

- Wingy Manone: 1 record

- Clyde McCoy: 1 record

- McKinney’s Cotton Pickers: 5 records

- Mills Blue Rhythm Band: 5 records

- Mills Brothers: 3 records

- Emmett Miller and his Georgia Crackers: 1 record

- Irving Mills & His Hotsy Totsy Gang: 5 records

- Borrah Minevitch: 1 record

- Miff Mole: 1 record

- Jelly Roll Morton: 11 records

- Bennie Moten: 29 records

- New Orleans Rhythm Kings: 1 record

- Red Nichols: 10 records

- Ray Noble: 2 records

- King Oliver: 10 records

- Raymond Parige: 1 record

- Jack Payne: 2 records

- Louis Prima: 1 record

- Don Redman: 5 records

- Leo Reisman: 1 record

- Harry Roy: 4 records

- Valaida Snow: 1 record

- Lew Stone: 2 records

- Joe Venuti: 5 records

- Fats Waller: 4 records

- Washboard Rhythm Band: 1 record

- Washboard Rhythm Boys: 2 records

- Washboard Rhythm Kings: 1 record

- Washboard Serenaders: 3 records

- Chick Webb: 1 record

- Paul Whiteman: 2 records

- Jay Wilbur: 1 record

- Sam Wooding: 6 records

And a few more remarks: Franz Wolff is obviously the most enthusiastic collector of Duke Ellington (and other predominantly African-American artists, including King Oliver, for example). The three records by Coleman Hawkins all date from 1933, i.e. before his long stay in Europe, and of course "Body and Soul" is missing, simply because he had obviously not yet recorded it when Blüthner compiled the notebook. Sam Wooding's six records all date from his European period and were recorded between 1925 and 1929 in Berlin, Paris and Barcelona. Only one of Benny Goodman's recordings is included. Carlo Boger had a preference for Red Nichols and Spike Hughes, as Blüthner recalled (Polster 1989: 33), which can also be seen from his record holdings: he owned eight of the ten Red Nichols records, as well as all eleven Spike Hughes records. Among the exotics on the list is Sol Hoopií, a representative of Hawaiian guitar music, who is listed with two recordings ("Farewell Blues", "Stack O'Lee Blues") that cannot be found elsewhere, at least not in the usual jazz discographies.

The entry about Emmett Miller and his Georgia Crackers is followed by a clear indication of the date of the notebook: "Saturday, March 1, 1936". On pages 71-75, Blüthner seems to have made detailed notes about music he had heard on the radio in March and April of that year. BBC? We do not know.

After looking through the notebook, one can see that it was an impressive collection. Mainly African American jazz, along with a few British bandleaders and relatively few German bands. If you read Blüthner's publications after the war, which were sent to the members of the Hot Club Berlin, for example, you can imagine how his taste was formed along these recordings.

And then I remember my last visit to him, during which at some point he put on a CD, Jimmie Lunceford, if I remember correctly. He still knew everything about this music. "My head is clear, only my body doesn't cooperate," he complained. Hans Blüthner never found out that some of his papers ended up at the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt in a roundabout way. But I'm sure he would have been pleased. (Photo: Hans Blüthner, Dieter Sternberg and Egon Wilrich, ca. 1936)

And then I remember my last visit to him, during which at some point he put on a CD, Jimmie Lunceford, if I remember correctly. He still knew everything about this music. "My head is clear, only my body doesn't cooperate," he complained. Hans Blüthner never found out that some of his papers ended up at the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt in a roundabout way. But I'm sure he would have been pleased. (Photo: Hans Blüthner, Dieter Sternberg and Egon Wilrich, ca. 1936)

Blüthner's notebook, which provides a glimpse into the Berlin jazz scene of the 1930s and the conscientiousness with which young jazz fans were dedicated to the music despite all the adversities of the time, has already been on display in several exhibitions, including one of Francis Wolff's photos for the Blue Note label at the Jewish Museum Berlin.

Wolfram Knauer (18. Dezember 2023)

Sources cited:

Blüthner 1947: Hans Blüthner: Die Berliner Hotfreunde, 17. Januar 1947 (Manuskript im Jazzinstitut Darmstadt)

Blüthner 1950: Hans Blüthner: Berlin und Jazz, 22. September 1950 (Manuskript im Jazzinstitut Darmstadt)

Blüthjner 1967: Hans Blüthner: Brief an Günter von Drenkmann, 23. Januar 1967 (Briefkopie im Jazzinstitut Darmstadt)

Blüthner 1981: Hans Blüthner: Brief an Hans Berry, 14. Juli 1981 (Briefkopie im Jazzinstitut Darmstadt)

Crosby 1953: Barney Crosby. Foreign Extraction, in: Theme, 1/3 (Oktober 1953): 23

Jockwer 2004: Axel Jockwer: Unterhaltungsmusik im Dritten Reich, Konstanz 2004 (PhD thesis: Universität Konstanz)

Lange 1966: Horst H. Lange: Jazz in Deutschland. Die deutsche Jazz-Chronik, 1900-1960, Berlin 1966 (Colloquium Verlag)

Kater 1992: Michael H. Kater: Different Drummers. Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany, New York 1992 (Oxford University Press)

Polster 1989: Bernd Polster: Swing Heil. Jazz im Nationalsozialismus, Berlin 1989 (Transit Buchverlag)

Schmid 2010: Thomas Schmid: Ein vergessenes Verbrechen. Der Berliner Kammergerichtspräsident Günter von Drenkmann war das erste Opfer des Linksterrorismus in der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik. In dieser Woche wäre er 100 Jahre alt geworden. Rückblick auf ein deutsches Leben, in: Die Welt, 13. November 2010 <https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/vermischtes/article10904029/Ein-vergessenes-Verbrechen.html>

Thiers 1960: Walter Thiers: Argentinien liebt Hot Jazz, in: Jazz Podium, 9/12 (Dec.1960): 262-263